Bubbly Puzzle

Want to play a game? Pop any bubble you like. When you pop a bubble, all the bubbles that contain it will also be popped (your needle must pierce them to get the target bubble, of course).

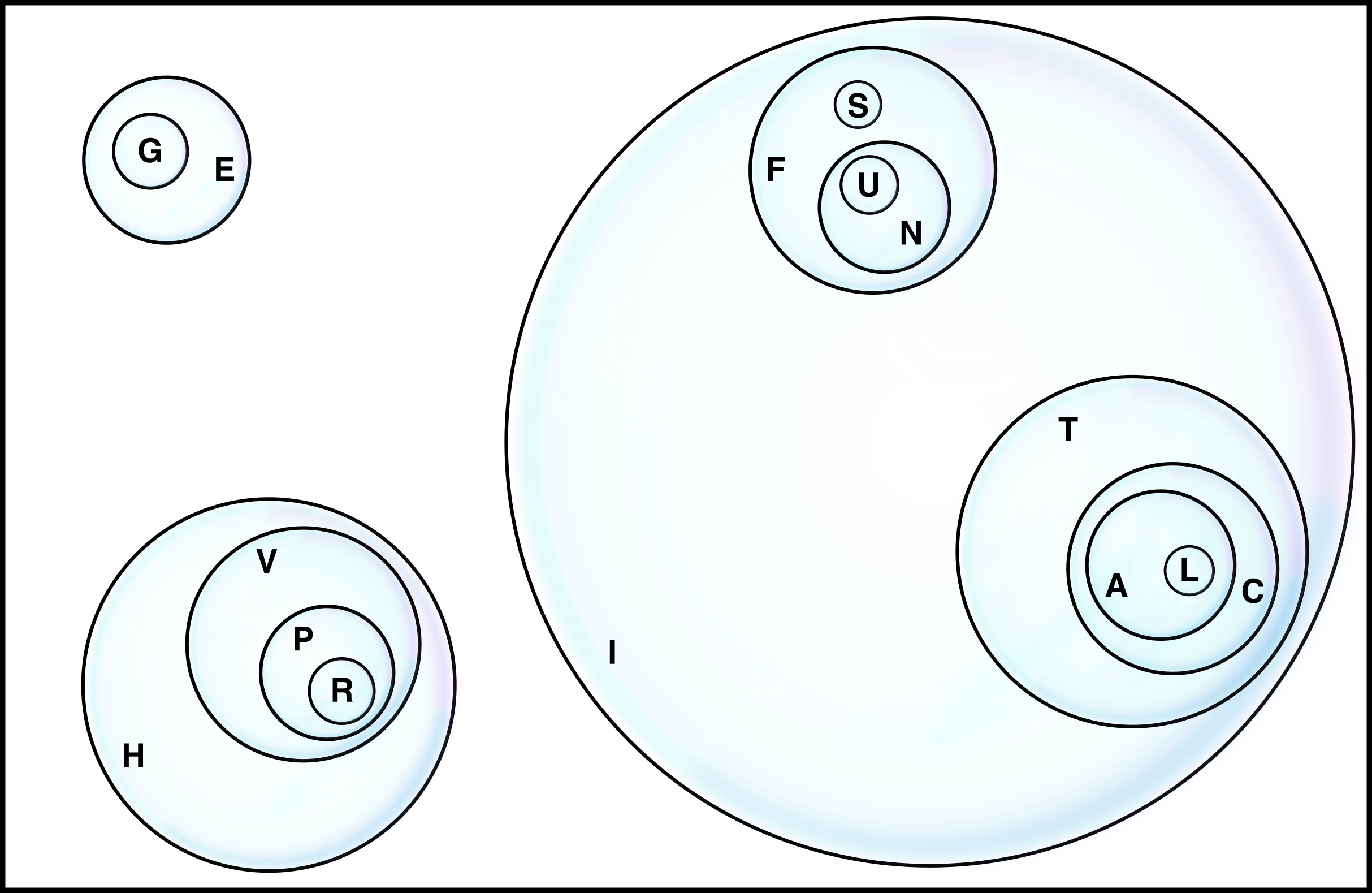

For example, if you want to pop the bubble containing U you will also pop the bubbles N, F and I. Then your opponent gets to pop a bubble of their choosing. The player who pops the last bubble wins. How do you know which bubble to pop?

This is the Bubbly puzzle from this year’s (2019) MIT Mystery Hunt. The goal of this puzzle was to find the correct winning moves for the first player in a number of increasingly complex bubble arrangements.

Our team ended up solving this puzzle by writing a brute-force computer program which used the Min-Max algorithm to find all the winning moves. But while working on this we noticed several interesting properties that kept me interested in the problem over the next few weeks. It reminded me of the classic mathematical game Nim and I wondered if I could find some elegant way to analyze Bubbly positions faster using Combinatorial Game Theory which I discovered a couple years ago in the book Winning Ways for your Mathematical Plays.

If you like these sorts of games, I suggest you play around with it for a bit, see if you can figure out the winning first moves in some of the example games (there are more than one winning move in all games). Then read on for some mathematical shortcuts.

Nim

Before analyzing Bubbly, let’s consider the simpler game: Nim. In the game Nim, there are some number of stacks of coins. On your turn you may remove as many coins as you like from one stack (but you must remove at least one coin from one stack). Like in Bubbly, the player who removes the last coin wins (sometimes the game is played with opposite rule, but we will not consider that version in this article). If you have not heard of Nim before, try playing some games and see if you can figure out any patterns.

It turns out that there is an elegant mathematical rule for how to play Nim optimally. You take the sizes of all the stacks and add them up using “Nimber addition”. One way to think about Nimber addition is to convert all the stack sizes into base 2 and then add them without carrying. So for example: If the stack sizes were 3, 4, and 5 then the Nimber sum is:

11

100

⊕ 101

-----

010If this Nimber sum is 0 on your turn, then you lose, any move you make can be countered by your opponent. If the sum is non-0, you can win by removing coins from one of the stacks enough to make the Nimber sum 0. (How do we know that there is always a way to remove coins from only one stack to cause the Nimber sum to be 0? Try it out yourself and then read this article for a more rigorous proof).

Sprague-Grundy theorem

It turns out that Nimbers will be quite useful to us. In fact, the Sprague-Grundy theorem tells us that every “impartial” 2-player “sequential game” of “perfect information” using the “normal play convention” can be evaluated as a single Nimber and multiple games can be added together using Nimber addition!

Let’s unpack a this with a few definitions first. A 2-player sequential game is one in which the players alternate turns, no player gets multiple turns in a row. Nim, Bubbly, Chess and most other games are sequential. Dots and Boxes is example of a game which is not sequential because filling a box gives the player another turn (although it could be converted into a sequential game by considering the whole sequence of extra turns as one move).

A game of perfect information means that there is no luck and no “hidden information” which one player knows, but the other does not. Nim, Bubbly, and Chess are all perfect information games. Poker, Backgammon, and Go Fish are examples of games without perfect information.

An impartial game is a game where the list of valid moves for either player is the same in all game positions. Nim, Bubbly and Dots and Boxes are all impartial games because the rules specify no difference between the moves that either player can make in a given position. In contrast, Chess, Go and Tic-Tac-Toe are not impartial games (they are called “partisan games”) because each player can only place (or move) their own pieces and not their opponent’s pieces.

The normal play convention is that the player who plays the last move (and thus forces their opponent to have no moves) is the winner. As discussed above Nim and Bubbly both follow this convention. The other games mentioned above do not strictly follow this normal play convention, having more complicated winning conditions (in fact, forcing your opponent to have no moves causes a Tie game in Chess). (You may question whether this is really a “normal” play given that so few games actually use this convention, but we digress).

It turns out that every game satisfying these conditions can be evaluated to be worth a specific Nimber and if you combine multiple games together, you can evaluate the total value by Nimber addition on the individual games (Just as we did for Nimber addition on the stack sizes in Nim). Let’s call these games Nimber games.

Adding two Games

What does it mean to add two games together? Well, it means that you play all the games at the same time, but on each person’s turn they must make a move in exactly one of the games. So, for example, if you break Nim up so that each stack is a separate game, you can see that the full game of Nim is exactly the sum of the individual stack games because the player must remove coins from exactly one stack/game.

Likewise in Bubbly, if you look at all the outside bubbles (ones not contained in any others (E, H and I in the picture above)) you can see that each of those can be broken off as it’s own game and the sum of those games will be the same as the value of the original game (because on every move in Bubbly, you must pick one outermost bubble and play a move inside of it).

Nimber Evaluation

This is all well and good, but now that we have separated the bubbly example above into 3 sub-games, how do you evaluate the Nimber value of each sub-game?

Well, 2 of those sub-games are actually rather easy to evaluate. For example, consider the top-left bubble (E with G inside), if we make a move in this bubble, there are only two options:

- Pop

Eand leave a single bubbleG - Pop

Gand leave nothing

This is exactly the same as a Nim stack of size 2 (which has only two options, remove one coin and leave a single coin; or remove all the coins and leave nothing). So this bubble group has Nimber value 2.

Likewise the group in the bottom left is 4 nested bubbles and allows us four options: Leave (3, 2, 1, or 0) nested bubbles. So this is the same as a Nim stack of size 4 and so it has Nimber value 4.

The big bubble on the right is clearly going to be the hardest and this one will require the MEX-rule to help us out.

MEX rule

For a given Nimber game position, consider the set of possible positions that can be reached after one move (this will be the same set for either player since we’re only talking about impartial games). For example, given a Nim stack of size 3, the possible next positions are {0, 1, 2} (meaning you can reduce this to a stack of size 0, 1 or 2).

The MEX rule says that in any Nimber game, the Nimber value is equal to the smallest Nimber not in the set of possible next moves (the Minimum EXcluded or MEX Nimber).

So for the example above the Nim stack of size 3 has MEX 3 since 3 is the smallest Nimber not in the set of next moves {0, 1, 2}.

Applying MEX to Bubbly

Let’s consider a more interesting example, the F bubble in the image above. This is one outside bubble with two stacks inside: A stack of size 1 (S) and a stack of size 2 (N-U). What are the possible next positions here:

- Pop

U: Leaves a single bubble (S). Nimber value = 1 - Pop

N: Leaves two single bubbles (S&U). Nimber value = 1 ⊕ 1 = 0 - Pop

S: Leaves a single stack of two bubbles (U-N). Nimber value 2 - Pop

F: Leaves a stack of one (S) & a stack of 2 (U-N). Nimber value 1 ⊕ 2 = 3

So the Nimber values of next positions are {0, 1, 2, 3} and so the MEX rule tells us that the F bubble with everything inside of it has Nimber value 4. For the remainder of this article, I’ll use X+ to denote the X bubble with everything inside of it and I’ll use nim(X+) to refer to the Nimber value of X+. We just showed that nim(F+) = 4.

We have enough tools now to evaluate the Nimber value for I+ (the entire I bubble and everything inside of it). The possible next positions are:

- Pop

I: Leaves theF+&T+.value = nim(F+) ⊕ nim(T+) = 4 ⊕ 4 = 0 - Pop something in

F+: LeavesT+and one of the positions listed above (S,S⊕U,N+orS⊕N+). We’ve already evaluated the Nimber values for all those sub-F+positions, those values are{0, 1, 2, 3}. So the value options when consideringT+arenim(T+) ⊕ {0, 1, 2, 3} = 4 ⊕ {0, 1, 2, 3} = {4, 5, 6, 7} - Pop something in

T+: LeavesF+and one of (C+,A+,Lor Empty). Value options =nim(F+) ⊕ nim({C+, A+, L, ∅}) = 4 + {3, 2, 1, 0} = {4, 5, 6, 7}

So the Nimber values of the next positions are {0, 4, 5, 6, 7} and thus the MEX rule evaluates nim(I+) = 1 (Note, the 4, 5, 6, 7 don’t effect this computation, we’re just looking for the minimum excluded number which is 1).

Finally we can evaluate the entire game’s Nimber value, which is: nim(I+) ⊕ nim(H+) ⊕ nim(E+) = 1 ⊕ 4 ⊕ 2 = 7.

How to win Bubbly

Ok, so now what? We know the Nimber value of this position is 7. Woohoo … wait … what does that mean again?

This value tells you whether or not the current play has a winning strategy in this position. If the Nimber value is 0, the currently player has no winning strategy (assuming perfect opponent play). If the Nimber value is not 0, then the current player does have a winning strategy. So what is it? Well the trick is to figure out how to pop a bubble and leave the Nimber value at 0 for your opponent. You could do this the brute-force way by just iterating through each bubble and see what Nimber score popping it leaves you with … or you could systematically go about it. For example:

- Pop something inside of

E+: LeavesH+⊕I+⊕ (something insideE+).nim(H+) ⊕ nim(I+) = 4 ⊕ 1 = 5, so the only way to get to 0 would be to have the Nimber value of something insideE+be 5. but the possible values after popping something inE+are{0, 1}, so that won’t work. - Pop something inside of

H+: LeavesE+⊕I+⊕ (something insideH+).nim(E+) ⊕ nim(I+) = 2 ⊕ 1 = 3. Aha, if we popHwe are left withV+andnim(V+) = 3, so poppingHis a winning move because it leaves a position with Nimber value 0 (nim(E+) ⊕ nim(I+) + nim(V+) = 0). - Pop something inside of

I+: LeavesE+⊕H+⊕ (something insideI+).nim(E+) ⊕ nim(H+) = 2 ⊕ 4 = 6. If we look back at the evaluation ofnim(I+)we can see that there are two ways to get to a Nimber value of 6 by popping something inside ofI: Either by popping something inside ofF+(S) or something inside ofT+(C).

So there are 3 winning moves from this position: C, H or S. If you find the rest of the winning moves on the MIT Mystery Hunt Puzzle, maybe you’ll spell something interesting :)