TM Transcripts

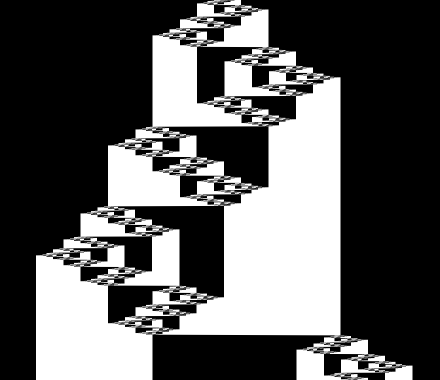

When we think about interpreting a Turing Machine’s behavior, we often think about visualizing the configuration history, for example in a space-time diagram like:

1RB0RF_1LC0RB_1RD0LC_1LE0RD_1RA0LE_1LD---

Images courtesy of @mxdys on bbchallenge Discord.

These visual representation can give a lot of hints about the large-scale behavior of the machines over long times, but they can also obscure the details of low-level behavior. In these large images we cannot even see where the TM head is, let alone what transitions it is following. What if instead of watching a TM, we listened?

If we closed our eyes or turned off the lights in the presence of a physical Turing Machine, we could not see these grand visual patterns, but instead, maybe with a little practice, we could learn to pick out the different sounds it made when executing different transitions?

Transcripts

You close your eyes and you hear A0 B0 C0 A1 B1 C0 A0 B0 C0 A1 B1 C0 A0 B0 C0 A1 B1 C0 .... Let’s call this the Transcript of the Turing Machine. This name has a double meaning, both the metaphorical meaning that it a transcription of the “sounds” of the TM, but also the literal meaning that it is a script of transitions. Am I leaning too much into this metaphor? If you want a more straightforward name, I believe that @mxdys calls this the Transition History of the TM.

Precisely, a Transcript is the sequence of (current state, read symbol) pairs over all steps of execution. We will use our standard notation of letters for states and digits for symbols so that one pair looks like C1 for example.

If a TM halts, then it has a finite transcript. For example, the BB(2) champion 1RB1LB_1LA1RZ has transcript A0 B0 A1 B0 A0 B1 and the BB(3) shift champion 1RB1RZ_1LB0RC_1LC1LA has transcript A0 B0 B1 C1 A0 B1 C0 C0 C1 A0 B1 C1 A0 B1 C1 A0 B1 C0 C0 C1 A1.

Repeated Motifs

If you were listening to this transcript played out as musical notes, you might notice the repeated sequence (or “motif”) C1 A0 B1 repeating several times throughout the BB(3) transcript. In fact, C1 A0 B1 corresponds to the rule:

and consecutive repeats of this motif correspond to the shift rule:

\[0 \; \text{C>} \; 1^n \to 1^n \; 0 \; \text{C>}\]Is this a coincidence?

Well, it turns out that every sequence of transitions from a transcript corresponds to some transition rule. For example, B1 C0 C0 C1 corresponds to the rule:1

and A0 B0 B1 C1 corresponds to the rule:

but neither of these sequences can be repeated since there is no way for the configuration afterward to match that before.

However, if we ever have a motif which repeats immediately, that means the end configuration is compatible with the start configuration (same state, no conflicting symbol context). In that case, either the rule is cycling in place or it is a shift rule.

Hearing Translated Cyclers

What do Translated Cyclers sound like? Well a translated cycler is, by definition, a situation where the TM is repeating the same finite sequence of transitions forever. Basically, translated cyclers are fancy shift rules that are trying to shift across the infinite blanks at one edge of the tape. We know what this sounds like, a motif repeated forever. But is it possible to know (just by listening) that this motif will repeat forever? For example, the transcript I mentioned first (A0 B0 C0 A1 B1 C0 A0 B0 C0 A1 B1 C0 A0 B0 C0 A1 B1 C0 ...) clearly has a repeated motif A0 B0 C0 A1 B1 C0, but will it repeat for the rest of time? In this case, this motif corresponds to the transition

and just liked we discovered in the last section, this corresponds to the shift rule

\[00 \; \text{A>} \; 00^n \xrightarrow{6n} 01^n \; 00 \; \text{A>}\]and this rule would be infinite if we were at the edge of the tape looking off into an infinite field of blank symbols (\(00 \; \text{A>} \; 0^\infty\)). But if we cannot see, and only hear there’s no way to know that we are not instead slowly running toward a wall, like

\[00 \; \text{A>} \; 00^{1000} \; 11 \; 0^\infty\]until we hit it … unless we make one small tweak to our transcript definition: the ability to distinguish the sound of an untouched blank symbol from that of a 0 previously written by the TM! Let us use the symbol _ to refer to the untouched blanks that the tape starts with and 0 to refer to the symbols written by a TM (including if the TM replaces a _ with a 0!). The TM cannot tell the difference between these, but with your finely tuned ear you can make out a slight difference in pitch.

Using your newly attuned ears you realize that the motif is actually A_ B0 C0 A1 B1 C_ and after examining the transition table you see that this corresponds to the rule

but now that you know that there were _s on the right, that means you know exactly what is to the right after this rule applies: blanks off to infinity, so this rule can be applied repeatedly forever and we have discovered a Translated Cycler! (Specifically 1LB1RB_1LC0RC_0RA---)

Deciding by Ear

We can see that in the previous example, we were able (with the help of the transition table) to deduce that this repeating motif was actually evidence of a translated cycle. But can we do this in general? It turns out that the answer is Yes! In fact, we do not even need access to the transition table! Furthermore, we can start listening whenever we want (it doesn’t have to be from the very start of the transcript). And even more-so, we can confidently declare it decided as soon as we hear the repeating motif twice in a row!

How can this be? Well, first let me describe the condition precisely: If any sequence of transitions in a transcript contains at least one _ and repeats itself exactly back-to-back, you can confidently declare that this is a Translated Cycler after only the second time through the sequence. We know from the “Repeated Motifs” section that any repeated motif must correspond to a shift rule (or cycle in place). But we also know that this motif contains a _ (notably also on the second time through) which means that (A) the TM is not cycling in place and (B) the shift rule is moving in the direction of new, untouched _s. Any shift rule which consumes _s is guaranteed to run forever, so this is a Translated Cycler!

Acknowledgements

I learned about this method for detecting Translated Cyclers via Transition History from bbchallenge Discord user @mxdys who shared it in a post on 11 June 2024 (Discord link):

Add a basic step to represent extending the tape edge. If we detect a non-nested for loop that has executed twice and contain a step for extending tape edge, then it’s a translated cycler.

This is one of the simpler cases of a broader class of TMs they call history-linear which involves finding various patterns in the transition history (what I call the transcript here). There is currently some discussion on the #inductive channel about whether more complex behavior, such as Bouncers can also be similarly “decided by ear”.

The listening metaphor is my own. Do y’all enjoy it when I make playful metaphors like this? Or does it confuse the idea?

@star mentions that they independently proved this “ages ago”. I do not know the history here, please share in the comments if you know more about the origins of this technique!

Footnotes

-

Note: Here I am using \((A0)\) to mean that the TM is in state

Aon symbol0. I choose not to use directed head notation here since this rule could apply equally well no matter which direction the head moved to reach this spot. ↩